Why No Team Has Ever Meant More to Me Than the ’80 U.S. Hockey Squad

- Mark Rosenman

- 5 days ago

- 14 min read

I have been extraordinarily lucky in my life as a sports fan and I say that fully aware that luck in sports fandom usually means willingly signing up for decades of emotional trauma interrupted by brief, glorious bursts of hugging and cheering with strangers in parking lots.

My first hit of championship euphoria came early. I was nine years old in 1969 an age when your biggest responsibility should be remembering where you left your baseball glove and somehow I stumbled into the sports equivalent of winning the lottery three times on the same scratch-off ticket. The Mets shocked the world, the Jets had already done their Broadway Joe thing, and the Knicks capped it off. At that age I assumed this was normal. I figured championships were just something that happened annually, like report cards or my mother reminding me to clean my room.

Reality, of course, showed up and reminded me that New York might be the capital of sports obsession but it’s not exactly the mecca of championships.

Still, there were more moments. The Knicks again in ’73. The Mets over the Red Sox in ’86 which was the reverse Benjamin Button experience, where you start the week youthful and end it needing blood pressure medication.And in 1994, the one that will stay tattooed on my soul forever: the Rangers finally breaking the 54-year curse. I have been fortunate enough not only to witness these moments, but to spend time interviewing players from those teams men whose accomplishments shaped the emotional calendar of my life.

And yet and this comes from a guy whose Mets obsession turned into the Kiner’s Korner, website and more than a few books about New York teams. I’ll confess something that may require surrendering my New York credentials: none of them hold a candle to the 1980 United States Olympic Hockey Team.

None.

Because this wasn’t just a championship. This wasn’t just my team beating your team. This was something bigger, louder, and far more improbable. It belonged to all of us at once. It was a moment that didn’t simply unfold on television it reached out and grabbed the country by the collar, shook us awake, and reminded us what belief looked like when it had absolutely no business showing up in the first place.

And for me, it never really let go.

So why this team? Why did a group of college kids skating around in Lake Placid carve out more permanent real estate in my heart than franchises I’d been emotionally chained to since childhood?

Timing — and context — had a lot to do with it.

February of 1980 found me at nineteen years old, in college, and like most nineteen-year-olds, living in that magical stage of life where you are technically an adult but functionally still convinced the world will sort itself out without requiring too much input from you personally. You’re aware of things but not yet weighed down by them. You hear the news, you read the headlines, but you haven’t quite absorbed what they mean for mortgages, retirement plans, or geopolitical stability.

Still, even through that youthful haze, it wasn’t hard to sense that this wasn’t exactly a banner moment for the United States. The Cold War wasn’t some abstract chapter in a history book — it was nightly television. The Soviet Union wasn’t just a rival; it was presented as the rival. Iran dominated headlines with hostage coverage that seemed endless. Inflation and gas lines were part of everyday conversation. Confidence as a national mood was… let’s call it under construction.

And back then, the Olympics actually carried a different emotional weight. They weren’t just another media event squeezed between streaming releases and trade deadlines — they felt global, communal, important.

I grew up on Olympic moments.

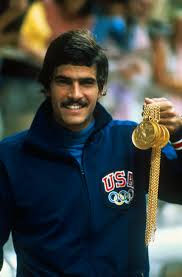

In 1972, it was Mark Spitz turning the Munich pool into his personal highlight reel — seven gold medals, seven world records, and that mustache that made every kid believe facial hair might be the secret to aquatic dominance. He didn’t just win; he dominated in a way that made the country swell with pride during a complicated and ultimately tragic Games.

By 1976, the spotlight shifted to the boxing ring in Montreal, where the U.S. team delivered a performance that still echoes through Olympic lore. Sugar Ray Leonard, brothers Leon and Michael Spinks, and Howard Davis Jr. weren’t just collecting medals — they were introducing themselves as the next generation of American sports icons. And for a kid growing up on Long Island, Davis winning gold added an extra layer of connection. He wasn’t just representing the country — he was representing the neighborhood. That’s the kind of thing that makes you sit a little closer to the television and feel like you’ve got a tiny share in the victory.

But 1980 felt different from the start.

For one thing and this mattered in my zip code hockey was everywhere. The Rangers were fresh off their run to the 1979 Stanley Cup Final, and the Islanders were revving up what would soon become a dynasty that made Nassau County feel like the center of the hockey universe. Around New York, the sport wasn’t niche — it was oxygen.

And the Olympic tournament itself was something else entirely then. This was before NHL players packed their bags for the Games. These weren’t global superstars or multimillionaires. This was a roster of amateurs — college players — guys who were, in many cases, my age or not far from it.

That created an instant connection.

They didn’t feel distant. They didn’t feel mythological. They felt relatable. Like they could’ve been sitting two tables over in the campus cafeteria arguing about classes or curfews — except they were about to skate into one of the most improbable chapters in sports history.

And then they started playing, and once they did, everything changed.

What unfolded in Lake Placid wasn’t cinematic because someone wrote it that way it was cinematic because nobody could have written it. Herb Brooks assembled a roster that didn’t resemble the polished machines skating for the Soviet Union. This was a patchwork of college kids who had barely learned each other’s tendencies before being thrown onto the world stage. Yet from the opening faceoff, you could sense something different brewing. It started with a tie with Sweden with Bill Baker scoring the tying goal as the extra skater in the final minute forcing a 2–2 tie with Sweden in the opening game. Little did we know at the time that tie allowed the team to eventually advance to the medal round.They beat Czechoslovakia, and began building belief with wins over Norway, Romania, and West Germany It wasn’t domination it was growth. You could almost watch the confidence form shift by shift, period by period, as the idea of competing quietly evolved into the idea of belonging.

Then came the game that froze time.

Facing the Soviet Union on February 22 — just thirteen days after being dismantled by them 10–3 at Madison Square Garden — the Americans weren’t expected to threaten, much less survive. This was a Soviet squad that hadn’t merely been winning international tournaments; they had been redefining them. Professionals in everything but official designation, they carried résumés longer than some of our roster’s driver’s licenses.

And yet, somehow, impossibly, the scoreboard tilted.

When Al Michaels asked if we believed in miracles, he wasn’t reaching for poetry he was giving voice to what millions of us were feeling in real time. That victory alone would have secured a permanent place in sports memory, but this team still had business left to finish. Two nights later they defeated Finland, completing the climb to gold and cementing themselves as something far greater than a hockey team. They became a moment — one stitched permanently into the national fabric.

Over the years, I’ve been fortunate to spend time talking with several members of that roster, conversations that revealed the human side of a story most of us first experienced through television and disbelief. Those exchanges didn’t just deepen my appreciation for what they accomplished; they reshaped my understanding of how it happened. And that’s where this story really begins.

If there was one voice that framed the entire experience for me, it was Herb Brooks. By that point, I had just started covering Mets games, interviewed legends like Frank Robinson and Willie Stargell, and yet, sitting across from Brooks in 1981 felt different — monumental in a way no baseball diamond, press box, or clubhouse has ever matched including sitting and talking one on one with Mark Messier or Tom Seaver. This was long before cell phones, selfies, or Instagram; what I wouldn’t give today to have a photo of the two of us from that afternoon, tangible proof of a conversation I’ve carried with me ever since. It was a moment I will forever cherish.

In 1981, Brooks came to speak at my college, and I had the good fortune and at nineteen, the confidence of someone who didn’t yet know enough to be intimidated to interview him for the campus paper, The Campus Slate. Somewhere between graduation, moves, and the general chaos of life, the audio and the article itself vanished into that black hole where cassette tapes and term papers go to live out their final days. I wish I still had them. But I remember the conversation and I remember him.

He was there promoting Miracle on Ice, the 1981 ABC docudrama about the U.S. Olympic team and its improbable run to gold, with Karl Malden portraying Brooks. And while the film celebrated the moment, Brooks spoke about something deeper — process, identity, and the deliberate construction of what he called an “uncommon” team.

Most of our discussion circled back to the themes that defined his coaching philosophy: preparation, sacrifice, and the elimination of ego in favor of collective purpose. He spoke about molding a roster of rival college players into a single unit, hammering home the idea that success demanded prioritizing the name on the front of the sweater over the one on the back. To him, talent alone wasn’t enough — belief, conditioning, and unity were non-negotiable.

His words echoed the mindset that would later become legendary:

“Great moments are born from great opportunity.”

“You were born to be a player. You were meant to be here. This moment is yours.”

“The name on the front is a hell of a lot more important than the one on the back.”

“You can’t be common. The common man goes nowhere. You have to be uncommon.”

“If you don’t want to skate in the game, we will skate after the game.”

These weren’t motivational poster slogans they were operating principles. Brooks believed in dragging players out of their comfort zones until potential turned into performance and doubt turned into conviction. Everything he did pointed toward one goal: making sure his team believed they could achieve something nobody else thought possible.

I asked him about one moment that fascinated me why he walked straight to the locker room after the victory over the Soviets rather than celebrating on the ice. His answer revealed as much about his character as any speech. He wanted that moment to belong entirely to his players. They were the ones who earned it, the ones who should feel the release and soak in the history. He also admitted to being emotionally spent humbled, overwhelmed and, in true Brooks fashion, already focused on the next objective. The job wasn’t finished. Gold still had to be secured.

And then there was the lighter side of the conversation the part that reminded you he wasn’t just a mythic figure in a tie behind the bench. He could not get past the casting of Karl Malden as himself in the film. Brooks pointed out, with equal parts disbelief and amusement, that Malden was 69 years old when portraying a man who had been 43 during the Olympics. He told me they nailed the casting of Jessica Walter as his wife — but Malden? He just couldn’t wrap his head around that one.

Even legends, it turns out, have a sense of humor about Hollywood.

That afternoon didn’t just give me quotes for a college newspaper. It gave me perspective on the mindset behind one of the greatest achievements in sports history a reminder that miracles don’t appear out of nowhere. They’re built, one demanding practice and one uncompromising standard at a time.

If Herb Brooks was the voice that framed the philosophy of the team, Mike Eruzione was the heartbeat on the ice the captain who embodied it. I’ve been fortunate over the years to interview Mike many times, from radio shows to Zoom calls with my Maccabi baseball teams, and each conversation only reinforced what anyone who followed that 1980 team already knew: this was a man forged by discipline, family, and a relentless belief in the improbable.

Mike often traced his mindset back to the lessons of his childhood in Winthrop, Massachusetts. Living in a three-family home, responsibility wasn’t optional — it was daily life. “Everybody was responsible for what they needed to do,” he told me once. “You take a work ethic environment with you, because you saw how hard our parents worked. My dad worked, my uncle worked… if you work hard, good things will happen to you. That’s been my approach in sports and life.”

Even his first skates, figure skates borrowed from his sister and adorned with pom-poms, were part of that early lesson in persistence. His parents supported him, but they demanded that he see things through. That ethic carried him through Boston University, where a chance encounter in a summer league game brought him to the attention of Jack Parker, who ultimately handed him his first real pair of ice skates and a path to collegiate—and eventually Olympic—greatness. “If I never played in that summer league game, I wouldn’t have been able to play on an Olympic team coming out of a Division II school,” Mike said.

By the time he was at the 1979 National Sports Festival — the proving ground for the Olympic team — Mike had already learned the value of preparation and perseverance. He tied for the tournament’s most points, won gold with the Great Lakes team, and walked into the banquet room to hear who had made the Olympic roster, acutely aware that his path to Lake Placid was far from guaranteed. And then there was Herb Brooks, whose methods were as intense as they were uncompromising. From grueling conditioning drills to the psychological games that kept the team focused, Brooks demanded they be ready to outlast and outwork the Soviets.

Mike’s reflections on that period reveal both the rigor and the humanity behind the myth:

“We were never concerned about what other teams were doing. You took care of what you had to do. That was Herb’s philosophy. Play your game, play your game.”

“Herb’s drills weren’t punishment. He wanted us to be in incredible shape. In the third period of every Olympic game, we outscored our opponents 16-3. That’s what the conditioning was about.”

“You were born to be a player. You were meant to be here. This moment is yours.”

When Mike scored the game-winning goal against the Soviets, it wasn’t just the culmination of a season or a tournament — it was a lifetime of preparation, sacrifice, and opportunity coalescing into one historic moment. But even then, Mike emphasizes, it wasn’t about personal glory. He reflects on the journey — from pom-pom skates to summer leagues, from Boston University to the national stage — as a funnel, a convergence of people, lessons, and relentless work. “Maybe I was born to be a player and meant to be there,” he said. “But every coach, teammate, and family member played a part in that moment.”

What emerges from these conversations is a vivid picture of a captain who understood his place not just on the ice, but in the narrative of a team, a nation, and a moment in history. Mike Eruzione didn’t just score goals; he carried the weight of expectation, the spirit of preparation, and the courage to seize what Brooks called an “uncommon” opportunity — and, in doing so, he helped turn a miracle into legend.

I have also spoken to many times over the years to Rob McClanahan, who also played 224 games in the NHL for the Buffalo Sabres, Hartford Whalers, and New York Rangers. But it is the memory of that February night in Lake Placid the Miracle on Ice that has defined his career and continues to resonate decades later. In my talks with McClanahan he often reflected on the experiences that shaped that team, the influence of coach Herb Brooks, and the enduring magic of a moment that captured the nation.

Herb Brooks, McClanahan explained, was the secret ingredient to the team’s success. “Herbie was ahead of his time. He forced us to do things as fast as we could so that when we got into a game, it seemed slower than it was in practice. He knew how to pick the right players. As Kurt Russell said in the movie, ‘I don’t want the best players, I want the right players.’ That’s exactly what Herbie did.”

Even during a grueling pre-Olympic schedule of 64 games against international and CHL competition, staying focused never felt like a burden. “It wasn’t hard to stay focused. It was the most fun I’ve ever had. We were 22-year-old kids on our own for the first time—didn’t have to go to school. All we had to do was focus on hockey. Playing against the CHL was terrific. Those games mattered, and teams that underestimated us paid the price.”

Yet there were humbling moments along the way, most notably the 10-3 loss to the Soviets at Madison Square Garden. “We were in awe of the Russians in every aspect—they just toyed with us. But Herbie had us prepared. He said, ‘If we play at the top of our game and get every break imaginable, we can win silver. Forget the gold.’ Then we saw the Soviets start to struggle, and he saw an opportunity. That’s when he began preparing us for victory.”

McClanahan remembers one defining moment against Sweden when he was injured in the first shift of the game, sidelined with a severe leg contusion. “Herbie came in and challenged me. I was shocked—I was ready to throw a punch. The movie shows part of it, but not everything. I followed him into the hallway, and I told him, ‘You’re not going to tell me if I can play. I’ll tell you.’ I went out and played. I wasn’t worth anything, but I played—and the rest is history.”

Looking at today’s Olympic hockey, McClanahan sees a stark contrast. NHL players arrive with little time to bond or practice together. “They’re phenomenal athletes, but they haven’t grown together over a full season. Some teams will click, some won’t. What we had—a team coming together for months, growing, bonding—that doesn’t exist today. It’s a completely different situation.”

Even so, the Miracle on Ice remains an enduring touchstone for fans and players alike. “People talk about that game against the Soviets. They remember where they were, like JFK or 9-11. It’s a feel-good story. Our kids see it too—they see the camaraderie. That moment will live forever.”

For McClanahan, the pride of that gold medal and representing the U.S. remains unmatched. “Playing in the NHL was a goal that became reality after college. But what I’m most proud of? Being a representative of the U.S. hockey team and accomplishing what we did under such great odds.” And at the heart of that success was Herb Brooks, the coach who could prepare his players to perform at their highest level when it mattered most. “For me, he was the best coach I ever played for. He knew how to get players ready at the most important time, and that’s what made us champions.”

Decades later, McClanahan continues to celebrate the moment, sharing it with fans, family, and even the next generation of athletes. “We’re still having fun with it. Giving me the opportunity to have my chest held high, to be proud—it was a rough time, and we brought such joy to so many. It was an amazing team, an amazing time, and one of my cherished sports memories.”

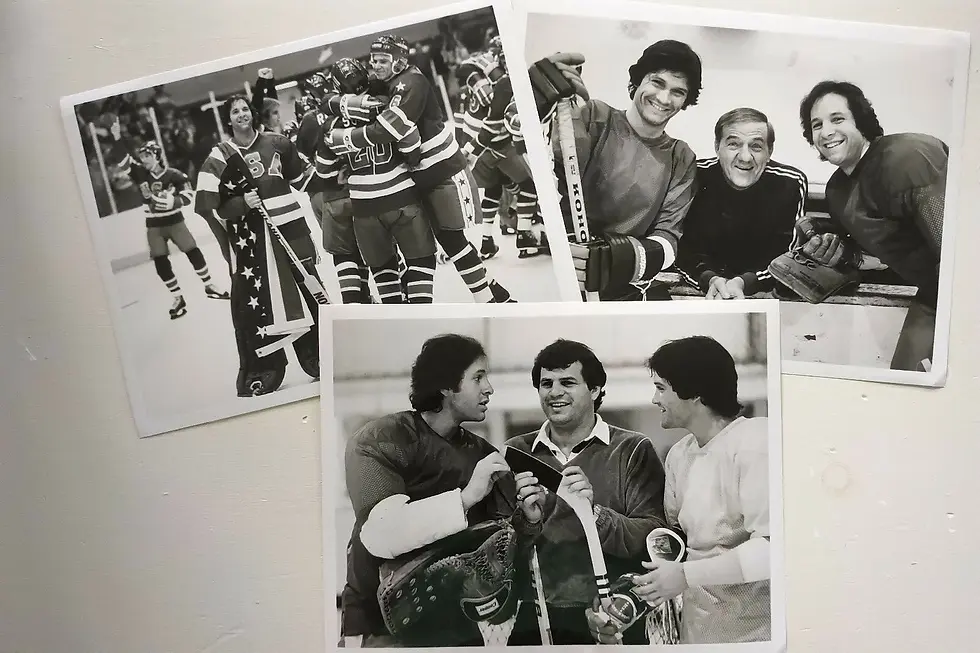

Over the years, I’ve had the privilege of speaking with so many members of that 1980 Olympic team—Craig Patrick, Mark Pavelich, Dave Christian, Neal Broten, Ken Morrow, Dave Silk, Jim Craig, Jack O’Callahan, and Bill Baker. Each conversation is a treasure trove of stories, memories, and laughter, and each one brings me back to that magical time in Lake Placid.

In 1993, I got a moment that felt almost like a pilgrimage. Thirteen years after the Miracle on Ice, I stepped onto that same hallowed sheet of ice in Lake Placid. For anyone who has followed hockey, it’s hard to overstate what that feels like—the ice itself seemed to hum with the memory of what had happened there, and being on it even once was a profound reminder of how extraordinary that team truly was.

That 1980 U.S. Olympic Hockey Team wasn’t just a collection of talented athletes; it was a group of young men who came together, against incredible odds, and achieved something that transcends sports. They were players who trusted one another, who believed in Herb Brooks, and who created a moment that continues to inspire generations. Watching them in action, reliving the games through stories, or seeing them on film, it’s impossible not to feel the thrill and the pride all over again.

For anyone who hasn’t yet seen them, I highly recommend both the new Netflix documentary Miracle: The Boys of ’80 and the Disney classic Miracle. Both, to be honest, still get me choked up. Even all these years later, there’s no question in my mind: that win over the Soviets, that gold medal, and that team represent maybe the single greatest sports moment of my lifetime. It’s a story of belief, of courage, and of the sheer joy of watching something impossible come to life.

In a country that feels like it’s lost its way, we need a team like the 1980 U.S. Olympic Hockey Team more now than ever.

100% agree. In a lifetime of unbelievable sports moments and memories, this one stands alone!